Warning! High Dimensions Ahead

Machine learning is often framed as finding surfaces (usually planes) that separate or fit points in some high dimensional space. Two and three dimensional diagrams are often used as an aid to intuition when thinking about these higher dimensional spaces. The following result (related to me by Marcus Hutter) shows that our low dimensional intuition can easily lead us astray.

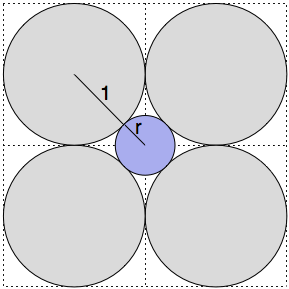

Consider the diagram in Figure 1. The larger grey spheres have radius 1 and are each touching exactly two other grey spheres. The blue circle is then placed so that it touches all four grey circles.

Pythagoras tells us that \(1^2 + 1^2 = (1+r)^2\) and so \(r = \sqrt{2} - 1 \approx 0.41\). Clearly then, the blue circle lies entirely within the square of width 4 containing all the grey spheres.

-

Figure 1: The blue circle in the middle touches each of the four identical grey circles.

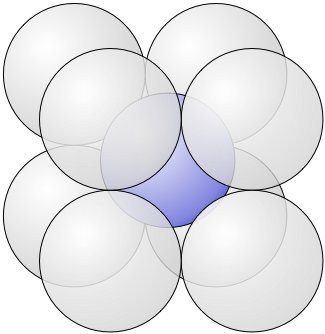

We can move to three dimensions and set up an analogue of the two dimensional situation by arranging eight spheres of radius 1 so they are touching exactly three other grey spheres.

As in the case with circles, we can place a blue sphere inside the eight grey spheres so that it touches all of them. In this case, the radius of the blue sphere can be found by solving \(1^2 + 1^2 + 1^2 = (1+r)^2\) and so \(r = \sqrt{3} -1 \approx 0.73\), thus it is still inside the cube of width 4 that holds all eight grey spheres.

-

Figure 2: The blue sphere touches each of the eight identical grey spheres.

It’s not too hard to convince yourself that we can carry on this construction through to higher dimensions.

In four dimensional space we would arrange 16 grey hyperspheres of radius 1 so that each is touching exactly four others. In this case, \(r = \sqrt{4} - 1 = 1\) and the blue hypersphere is the same size as the grey ones. Going up again to five dimensional space, we would have 32 hyperspheres, each touching five others. Following the pattern, in this case \(r = \sqrt{5} - 1 \approx 1.23\). and the blue sphere is larger than the grey spheres in this case but still within the hypercube of width 4 that contains all 32 grey hyperspheres.

The pattern should now be apparent. In n-dimensional space there will be \(2^n\) grey hyperspheres of radius 1 that touch \(n\) other hyperspheres and the radius of the blue sphere that touches all of them will be \[ r = \sqrt{n} - 1. \]

At this point Dorothy turns to her canine companion and says, “We are not in three dimensional Kansas anymore, Toto.”

The blue sphere that sits in the centre of all the grey ones will have a radius that increases without bound. A particularly curious thing happens when we construct the 9-dimensional case. The radius of the blue hypersphere is \(\sqrt{9} - 1 = 2\) and so touches the faces of the hypercube that contains all the grey hyperspheres.

Stranger still, once we are in 10 dimensional space or higher, parts of the blue hypersphere will hang outside the box holding all the grey ones.

Thinking about the relative volume of the containing box and the grey spheres gives us some insight into what is happening. In \(n\) dimensions the volume of the containing box is \(4^n\) while the volume of a \(n\)-ball with radius 1 is \[ \frac{\pi^{\frac{n}{2}}}{\Gamma(\frac{n}{2}+1)} = \begin{cases} \displaystyle \pi^k / k! ,& n=2k \\ \displaystyle 2^{2k+1}k!\pi^k / (2k+1)! ,& n=2k+1 \end{cases} \] where \(\Gamma\) is the generalised factorial function.

For simplicity let us only consider the even dimensional cases where \(n=2k\). Here, the total volume of the \(2^n\) grey hyperspheres is \(2^{2k} \pi^k / k!\) and so the proportion of the box occupied by the grey hyperspheres is \[ \frac{2^{2k}\pi^k}{4^k k!} = \left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)^k / k! \] Since factorials are faster growing than exponentials the total proportion of volume occupied by the grey sphere in the box goes to zero as the dimension increases. In effect, the grey hyperspheres are “disappearing” relative to the containing box, leaving more room for the blue sphere to fill.

The moral of this story should be familiar to anyone in machine learning: generalising from a handful of examples is a bad idea. What seems obvious in two and three dimensional space does not hold in 10 dimensions or higher.

Mark Reid January 25, 2009 Canberra, Australia